History

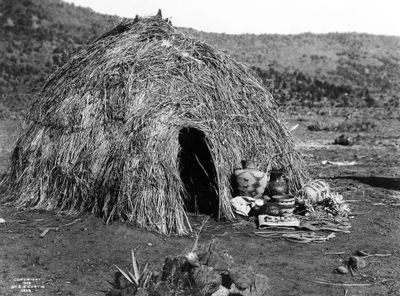

APACHE TRIBE

Mexicans called them Apaches—Enemy. They called themselves The People—Tinde'.

As long as anyone could remember, first the Spaniards, then the Mexicans had been at war with the Apaches. Neither side had any desire to change things. It was kill or be killed, steal or be stolen from, burn or be burned out, whenever they met. Wrongs on both sides ran too deep. It was a fight to extinction.

In 1853, the Mexican Government placed a bounty on Apache scalps. They paid twenty-five dollars for a child’s scalp, fifty for an Apache woman’s, and one hundred for an adult male’s. But who could tell from a scalp lock of long black hair the sex or age of the Indian scalped, or whether the scalp might even be that of a Mexican peon. Apaches knew that to the bounty hunter, anyone—young or old, male or female—was fair game.

Then a new breed called Americans came into the West. They came in all sizes and colors, some good, some bad. At first they merely passed through the Arizona Territory in 1849 on their way to the California gold fields. They didn’t scare as easily as the Mexicans. Many could hunt and live off the land like an Apache. They trapped and traded, prospected and homestead, and looked like they planned to stay.

In the beginning, the Americans were too few in number to be considered a threat, and the Apache tried to get along with them. At one point, the Apaches had even hoped the Pindo-Lik-O-Yes or White Eyes would help them in their fight with the Mexicans.

Instead, the United States made peace with Mexico, and the two countries changed their boundaries. The Bartlett Commission of 1851 went through the New Mexico and Arizona Territory to draw the new line across the sands. Though they looked for it, the Apaches could never find this line. What was once Mexico’s had now become the property of the United States; but those to whom the land truly belonged were never given a thought. No one asked their permission to hunt on their lands, kill their game, to plunder the earth’s bounty for ore or to ruin their way of life. They just did it.

Aided by the very nature of their terrain, the Apaches resisted the whites’ advance longer than did any other Indian nation. The years between 1861 and 1874 became known as the Cochise War. Other names became dreaded household words as well: Mangus Coloradas, Victorio, and Geronimo.

With only a few hundred warriors, the Apaches still held off five Civil War generals, five thousand trained troops and scouts, and cost the United States millions of dollars in men and material.

NAVAJO TRIBE

In 1860, because of complaints about Navajo raids on mining camps and ranches in New Mexico, Col. Kit Carson was called in to U.S. Army Headquarters by General James Henry Carleton. It was Carleton’s shortsighted wish to put all the Navajos on a reservation and teach them the benefits of becoming more like the white man. He wanted them to learn to grow crops, become Christianized and civilized to fit into the white man’s society. Kit Carson, having made friends with the Navajos, feared it would not be an easy task. Nor was it. He finally resorted to a “scorched earth” policy where he burned out villages, farm plots, peach orchards, killed livestock or took them for his army, and literally drove 7,000 Navajos south to a barren piece of land called the Bosque Redondo. At least 200 died during the 18-day, 300-mile (500-km) trek on the Pecos River. Eventually the Navajos would call this march “The Long Walk.”

SHOSHONE TRIBE

After I finished my Apache and Navajo series, I decided to research another tribe that I was not as familiar with. Over the years I have visited several Native American Reservations and learned more about their culture and heritage. One of the tribes not written about as much or made into movies was the Shoshone Indians in parts of Wyoming, Montana, and Utah.

There were two main chiefs among the Shoshone, Chief Washakie of the Eastern Band, and Chief Pocatello of the Western Band. They differed greatly on how to treat the invading white man coming into their territory. Chief Washakie wanted to try to keep peace with the wagon trains heading through his land to Oregon and even made a pact to protect them along the trail. Saying, “it was easier to make friends than to make war.” Chief Pocatello, on the other hand, wanted to annihilate every white man, woman, and child who come into his territory.

Chief Washakie was born in 1804 in Montana. He became good friends with the mountain man, trapper, and trader, Jim Bridger, who settled in the territory and had a fort built to accommodate the annual rendezvous and to supply those immigrants traveling west. The chief learned English and would come to understand the turning of the tide and what was coming to his land and people. The Shoshone way of life was in for a major change and Washakie foresaw it. The great Shoshone leader, once a fearless and battle-hardened warrior, pressed for a peaceful existence with neighboring Indian nations, and helped guide his people into the formation of the Shoshone Reservation. He dealt with the white man on an equal footing of respect and friendship, and eventually ceded lands for the Shoshone near Thermopolis that contained healing waters.

No one was ever more revered by his people. He died at the age of 102 on the Wind river Reservation on February 22, 1900.

Copyright © 2020 Carol Ann Didier - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy Website Builder